Abstract

This paper reflects on the needs for close interaction between psychiatry and all partners in international mental health for the improvement of mental health and advancement of the profession, with a particular view to the relationships between mental health, development and human rights. The World Health Organisation identifies strong links between mental health status and development for individuals, communities and countries. In order to improve population mental health, countries need effective and accessible treatment, prevention, and promotion programmes. Achieving adequate support for mental health in any country requires a unified approach. Strong links between psychiatrists, community leaders and patients and families that are based on negotiation and respect, are vital for progress. When strong partnerships exist, they can contribute to community understanding and advancement of psychiatry. This is the first step towards scaling up good quality care for those living with mental illnesses, preventing illnesses in those at risk, and promoting mental health through work with other community sectors. Partnerships are needed to support education and research in psychiatry, and improvements in quality of care wherever psychiatry is practiced, including primary health and community mental health services, hospitals and private practice. There are important roles for psychiatry in building the strength of organisations that champion the advocacy and support roles of service users and family carers, and encouraging partnerships for mental health promotion in the community.

Keywords: Human rights, Mental health promotion, Psychosocial programmes, Prevention, Resilience, Well-being

Introduction

Dr Arthur Kleinman illuminates the moral failure of communities in all parts of the world to recognise the humanity and relieve the suffering of people living with mental disorders (Kleinman, 2009[12]). Much of the suffering arises from the experiences of being treated as a non-person. For many people this means cruelty, neglect and exclusion from family and community life. Finding ways to change this situation is the combined concern of psychiatry and international mental health.

The concerns of psychiatry and other partners in mental health internationally and within countries are vitally interconnected. Ensuring that they work closely together is important for improving mental health and redressing these wrongs. Achieving support for mental health requires a united voice along with opportunity for the various groups to promote their legitimate interests.

Significant barriers to the success of partnerships in doing this continue to include the lack of mutual understanding and respect between groups. It is essential that those points of difference or confusion are identified and addressed. Psychiatrists and their associations bring a unique perspective based on understanding the individual and environmental contributions to mental health and illness; and intimate knowledge of the consequences of mental illness for health, productivity and quality of life. Essential contributions equally come from service users and their families, practitioners from other professions, and government and non-government organisations.

This paper reflects on the needs for close interaction between psychiatry and all partners in international mental health for the improvement of mental health and advancement of the profession, with a particular view to the relationships between mental health, development and human rights.

Mental health, development and human rights

A growing evidence base indicates that mental ill-health and poverty interact in a negative cycle in low-income and middle-income countries. A review in the latest Lancet series on mental health reaches this conclusion (Lund et al., 2011[13]). Another review in the same series supports the call “to scale up mental health care, not only as a public health and human rights priority, but also as a development priority” (Eaton et al., 2011[5], p. 7). The World Health Organization identifies strong links between mental health status and development for individuals, communities and countries (WHO MIND, 2012[24]). Mental health is associated with positive development outcomes and is fundamental to coping with adversity, whereas poor mental health impedes an individual’s capacity to realize his or her potential and make a contribution to the community. In order to improve population mental health, countries need to make effective treatment, prevention, and promotion programmes available to all who need them (WHO, MIND, 2012[24]).

Although effective treatments exist for many people with mental, neurological and substance use disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, epilepsy, dementia and alcohol dependence (Patel and Thornicroft, 2009[18]), treatment and care are often inaccessible or unavailable. This is most marked for those people with greatest needs whether they are young or older (Patel and Thornicroft, 2009[18]). To change the situation, there is a need to support the central place of mental health in general health care worldwide, building on the growing evidence about the way that psychiatric and medical illnesses are intertwined and mutually influential. Good mental health care in primary care, general hospitals and community based mental health services requires support for development of the workforce and other resources (WHO, 2001[25]; Patel and Thornicroft, 2009[18]). The psychiatrist as part of a multidisciplinary team can provide leadership and scientific rigour to guide service delivery (Herrman et al., 2010[8]). The training, supervision and consultation with other professional and lay workers in primary care is an important way to extend support for mental health care in low-resource settings (Patel and Thornicroft, 2009[18]). This can also be a very useful strategy in higher income countries. Research into health system changes is vital, together with investigation of the social exclusion that accompanies mental and behavioural disorders in all societies (Eaton et al., 2011[5]; Patel and Thornicroft, 2009[18]; Drew et al., 2011[4]).

Recently the global research community articulated the need for urgent action to improve the lives of people with, or vulnerable to, mental illnesses. A consortium of researchers, advocates and clinicians supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in Bethesda, Maryland, and the Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases (GACD) announced the grand challenges in global mental health (Collins et al., 2011[3]). The first challenge is to invest in research that uses a life-course approach, beginning in childhood when many mental illnesses have their beginnings, and when risk factors for illnesses later in life- such as family violence in the home- are established. This work could allow for interventions to reduce the incidence of illness such as depression, anxiety and substance abuse. Second, social exclusion, discrimination and a health system that is not user-friendly cause suffering that could be minimised by integrating care for mental illnesses into chronic disease care. Third, evidence based strategies whether psychosocial or pharmacological, simple or complex, are needed to guide clinicians, planners and policy-makers. Finally, environmental exposures, especially poverty, war and natural disasters, by mechanisms that are poorly understood, can precipitate or magnify mental illnesses (Singh and Singh, 2008[21]).

Mental health and development are linked through broader influences in non-heath sectors. Mental health can be promoted through the work of education, employment and other community sectors. Improved mental health can in turn assist the sectors with their own outcomes (Beddington et al., 2008[1]; Herrman et al., 2008[9]). Psychiatrists and public health experts can recommend strategies for promoting mental health in the work of these sectors; and support the development of partnerships needed to accomplish the work and its evaluation (Saxena et al., 2006[20]). Government policies and work with other sectors in cost-effective public health actions to support parenting, and to work in schools, at workplaces and in older age populations can improve the population’s mental health status. There is growing evidence to support this assertion in a number of countries and a need to encourage adaptation and evaluation of programmes in others (Jane-Llopis et al., 2011[11]).

Youth mental health

The gap between unmet need and access to care for mental ill-health is wider for adolescents and young people aged 12-25 years than for any other age group worldwide (McGorry et al., 2011[14]; Patel et al., 2007[17]; Resnick et al., 2012[19]). This age group is the peak time of onset for many mental disorders including mood, substance abuse and psychotic disorders. Effective interventions in primary or specialist care are likely to be most cost-effective at this age (Bloom et al., 2011[2]). Strong opportunities also exist for prevention and health promotion action in other settings such as schools and the internet. Yet in most countries there are few opportunities for young people and their families to gain access to treatment and care for mental ill-health and preventive interventions (Morris et al., 2011[16]). This is especially important for young people exposed to trauma and adversity (Tol et al., 2011[22]). Few countries give sufficient attention to supporting the mental health of young people and few have developed policies and programmes to support this (Morris et al., 2011[16]; WHO, 2012[26]).

Policy and practice changes suitable for each country have two essential starting points: (1) improved understanding of youth mental health within communities; and, (2) involving young people and their families in decisions that affect them. Using information technology to assist care is another desirable feature of modern service development suitable for any environment. As an example of innovation and service reform, recent developments in Australia have led to the construction of a series of policy frameworks and new programmes to address this major public health issue. Headspace, the National Youth Mental Health Foundation, was established in 2006, with the mission to promote and support early intervention for young people with mental health problems. A major part of the mandate is to establish youth-friendly, highly accessible centres that target young people’s core health needs by providing a multidisciplinary enhanced primary care structure with close links to locally available specialist services and community organisations (McGorry et al., 2007[15]). Currently, there are 40 Headspace centres across Australia, with a further 50 centres due to commence services throughout 2012-15. A similar initative, Headstrong, has been established in Ireland, and currently has five centres operating (Illback and Bates, 2011[10]).

Partnerships in mental health

Strong links between psychiatrists, community leaders and patients and families that are based on negotiation and respect, are vital for progress. When strong partnerships exist, they can contribute to community understanding and advancement of psychiatry. This is the first step towards scaling up good quality care for those living with mental illnesses, preventing illnesses in those at risk, and promoting mental health through work with other community sectors (Herrman, 2010[7]).

Psychiatrists, governments and professional groups in a range of countries increasingly support the inclusion of service users and carers in decisions about treatment and rehabilitation, service development, research and policy. However, service users and carers worldwide have the regular experience of stigma and discrimination in the community, as well as poor access to dignified care for mental and physical health problems. Building on work in several countries, a World Psychiatric Association (WPA) taskforce recently developed recommendations for the international mental health community on best practices in working together between service users, family carers and professionals (Herrman, 2010[7]; Wallcraft et al., 2011[23]). The WPA is an association of national psychiatric societies committed to increasing the knowledge and skills necessary for work in the field of mental health and care for people with mental illnesses. It represents 200,000 psychiatrists in 117 countries and is in official relations with the WHO.

The taskforce had the remit to create recommendations for the international mental health community on how to develop successful partnership working. The work began with a review of literature on service user and carer involvement and partnership. This set out a range of considerations for good practice, including choice of appropriate terminology, clarifying the partnership process and identifying and reducing barriers to partnership working. Based on the literature review, on the shared knowledge in the taskforce and a wide consultation, a set of ten recommendations for good practice was developed (Wallcraft et al., 2011[23]).

The recommendations begin with respect for human rights as the basis for successful partnerships. Other recommendations include: clinical care is best done in collaboration between service users, carers and clinicians; as are education, research and quality improvement. Three of the recommendations have particular relevance for national and international psychiatric associations:

- (i)

The international mental health community should promote and support the development of users’ organisations and carers’ organisations;

- (ii)

Improving the mental health of the community should be a fundamental condition for formulating policies to support economic and social development. This requires participation of all sectors of the community;

- (iii)

International and local professional organisations, including WPA through its programmes and member societies, should seek the involvement of consumers and carers in their own activities (Wallcraft et al., 2011[23]).

A paragraph based on the recommendations was added in 2011 to WPA’s fundamental ethical guidelines for psychiatric practice, the Declaration of Madrid, (1996, and enhanced 1999, 2002, 2005; see, WPA, 2005[27]). Each country will need specific guidelines and projects to apply these recommendations and contribute to worldwide learning. Supported decision making to enhance recovery for people with mental illnesses is an important topic that requires partnership work.

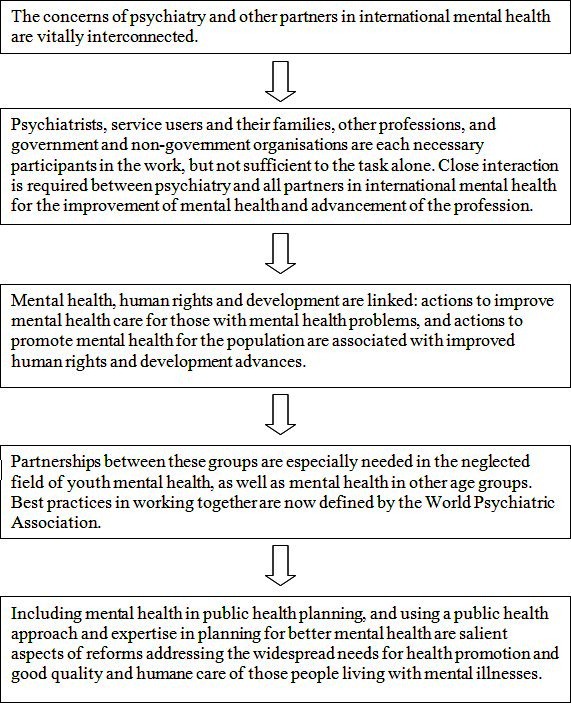

Conclusions [See also Figure 1: Flowchart of paper]

Figure 1.

Flowchart of paper

From the viewpoint of a public health physician it seems the natural order that partnerships are essential for improving mental health worldwide (Herrman, 2007[6]). Most actions that are important to people’s lives and health require the endorsement and participation of all affected for their success. For mental health, these actions include policy and resources to support the central place of psychiatry in general health care. Partnerships are needed to support education and research in psychiatry, and improvements in quality of care wherever psychiatry is practiced, including primary health and community mental health services, hospitals and private practice, in diverse communities and under adverse conditions. Finally, there are important roles for psychiatry in building the strength of organisations that champion the advocacy and support roles of service users and family carers, and encouraging partnerships for mental health promotion in the community. Strong links between psychiatrists, community leaders, patients and families, based on negotiation and respect, are vital to reduce stigma, increase community understanding and advance psychiatry.

Take home message

The new WPA recommendations on working with service users and family carers provide an innovative framework to support, evaluate and learn from local projects, and build experience on working in partnership to improve mental health.

Questions raised by this Paper Raises

What are the main interest groups included in the international mental health community?

What are the benefits of psychiatry partnering closely with these groups?

What are the barriers to these partnerships succeeding?

What are best practices for psychiatrists, service users and family carers in working together?

About the Author

Helen Herrman is Professor of Psychiatry at Orygen Youth Health Research Centre and the Centre for Youth Mental Health, The University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and Director of the World Health Organisation Collaborating Centre for Mental Health in Melbourne. She is a psychiatrist and public health physician. She holds an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellowship, and is Honorary Fellow of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), having served as WPA Secretary for Publications 2005-2011

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: The author has no financial disclosures related to the material in the article.

Conflict of interest: None declared

Declaration

This work is the original, unpublished work of the author. It has not been published or submitted for publication elsewhere.

CITATION: Herrman H. Reflections On Psychiatry And International Mental Health. Mens Sana Monogr 2013;11:59-67.

Peer Reviewers for this paper: Abhijit Nadkarni DPM, MRCPsych; Srinavasa Murthy MD

References

- 1.Beddington J, Cooper CL, Field J, Goswami U, Huppert FA, Jenkins R, et al. The mental wealth of nations. Nature. 2008;455:1057–60. doi: 10.1038/4551057a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jané-Llopis E, Abrahams-Gessel S, Bloom LR, Fathima S, et al. The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases. Geneva: World Economic Forum; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, March D, Insel TR, Daar AS, et al. Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature. 2011;475:27–30. doi: 10.1038/475027a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drew N, Funk M, Tang S, Lamichhane J, Chavez E, Katontoka S, et al. Human rights violations of people with mental and psychosocial disabilities: An unresolved global crisis. Lancet. 2011;378:1664–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61458-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eaton J, McCay L, Semrau M, Chatterjee S, Baingana F, Araya R, et al. Scale up of services for mental health in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2011;378:1592–603. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60891-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrman H. What psychiatry means to me. Mens Sana Monogr. 2007;5:179–87. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.32162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herrman H. WPA Project on Partnerships for Best Practices in Working with Service Users and Carers. World Psychiatry. 2010;9:127–8. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrman H, Brownie S, Freidin J. Leadership and professionalism. In: Bhugra D, Malik A, editors. Professionalism in Mental Health: Experts, Expertise and Expectations. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrman H, Moodie R, Saxena S. Mental health promotion. In: Heggenhougen K, Stella Q, editors. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. San Diego: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 406–18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Illback RJ, Bates T. Transforming youth mental health services and supports in Ireland. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2011;5(Suppl 1):22–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2010.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jane-Llopis E, Anderson P, Stewart-Brown S, Weare K, Wahlbeck K, McDaid D, et al. Reducing the silent burden of impaired mental health. J Health Commun. 2011;16(Suppl 2):59–74. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.601153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleinman A. Global mental health: A failure of humanity. Lancet. 2009;374:603–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61510-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lund C, De Silva M, Plagerson S, Cooper S, Chisholm D, Das J, et al. Poverty and mental disorders: Breaking the cycle in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2011;378:1502–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60754-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGorry PD, Purcell R, Goldstone S, Amminger GP. Age of onset and timing of treatment for mental and substance use disorders: Implications for preventive intervention strategies and models of care. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:301–6. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283477a09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGorry PD, Tanti C, Stokes R, Hickie IB, Carnell K, Littlefield LK, et al. Headspace: Australia’s National Youth Mental Health Foundation – where young minds come first. Med J Aust. 2007;187(7 Suppl):S68–70. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris J, Belfer M, Daniels A, Flisher A, Ville L, Lora A, et al. Treated prevalence of and mental health services received by children and adolescents in 42 low-and-middle-income countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:1239–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, McGorry P. Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet. 2007;369:1302–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel V, Thornicroft G. Packages of care for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Resnick MD, Catalano RF, Sawyer SM, Viner R, Patton GC. Seizing the opportunities of adolescent health. Lancet. 2012;379:1564–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxena S, Paraje G, Sharan P, Karan G, Sadana R. The 10/90 divide in mental health research: Trends over a 10-year period. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:81–2. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.011221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh AR, Singh SA. Diseases of poverty and lifestyle, wellbeing and human development. Mens Sana Monogr. 2008;6:187–225. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.40567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tol W, Barbui C, Galappatti A, Silove D, Betancourt T, Souza R, et al. Global Mental Health 3: Mental health and psychosocial support in humanitarian settings: Linking practice and research. Lancet. 2011;378:1581–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61094-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallcraft J, Amering M, Freidin J, Davar B, Froggatt D, Jafri H, et al. Partnerships for better mental health worldwide: WPA recommendations on best practices in working with service users and family carers. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:229–36. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO. MIND. 2012. [Last accessed on 2012 Sept 13]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/en .

- 25.The World Health Report 2001. Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adolescent mental health: mapping actions of nongovernmental organizations and other international development organizations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 27.WPA. Madrid Declaration on Ethical Standards for Psychiatric Practice. 2005. [Last accessed on 2012 Sept 13]. Available from: http://www.wpanet.org/detail.php?section_id=5andcontent_id=48 .