Abstract

In this paper, I compare three different views of the relation between subjectivity and modernity: one proposed by Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, a second by theorists of institutionalised individualisation, and a third by writers in the Foucaultian tradition of studies of the history of governmentalities. The theorists were chosen because they represent very different understandings of the relation between contemporary history and subjectivity. My purpose is to ground psychoanalytic theory about what humans need in history and so to question what it means to talk ahistorically about what humans need in order to thrive psychologically. Only in so doing can one assess the relation between psychoanalysis and progressive politics. I conclude that while psychoanalysis is a discourse of its time, it can also function as a counter-discourse and can help us understand the effects on subjectivity of a more than thirty year history in the West of repudiating dependency needs and denying interdependence.

Keywords: Character, dependency, Modernity, Normative unconscious processes, Psychoanalysis and politics, Subjectivity

Introduction

In a recent article, Elisabeth Young-Bruehl (2011[29]) writes about various attempts that have been made to synthesise psychoanalysis and political progressivism since Freud. The story Young-Bruehl tells is one version of how to understand the relation between subjectivity and modernisation in the Western world, a view that focusses squarely on a universal vision of what humans need in order to thrive and on countering all forms of social exclusion. In this essay, I shall place Young-Bruehl’s historiography in juxtaposition to two other very different stories about the history of subjectivity and modernity. These versions of history do not talk about what humans need. Instead, they tell a story about how social changes and social agendas produce individuals whose needs and character emerge from what it takes to thrive in the particular social and political conditions of Western modernity (conditions they do not necessarily equate with “democracy”). The first such version is proffered by theorists of “risk society” and “institutionalised individualisation” (Beck, 1999[2]; Beck and Beck-Gernsheim, 2002[3]), who argue that post-war modernity is primarily characterised by the continual disembedding of subjects from any kind of “tradition” to which they might have recourse in trying to ground their decisions about how they ought to live. The second derives from the work of Foucault and focusses on the role psychological sciences have played in what Rose (1989[25]) has called “governing the soul,” an increased interference by experts in the conduct of the daily private lives of families and individuals (with particular focus on subjectivities produced by welfare states). More recently, theorists in this same Foucaultian tradition have pointed to a historical shift away from the kind of welfare state subjective practices Rose discussed. These authors, trying to understand neoliberal versions of subjectivity, have highlighted cultural and political demands on subjects to adopt practices that will enable them to become the “enterprising” selves necessary for functioning well in neoliberal social and economic conditions (see, for example, Binkley, 2009[4]; du Gay, 2004[7]). These latter writings are not psychoanalytic, but I draw on them to elaborate my own psychoanalytic understanding of relations between social character, historical conditions in the contemporary West, and what humans might need to thrive. I juxtapose these different perspectives on our current situation in the West in order to raise questions about what humans need, about what psychoanalysis might contribute to the making of a more politically progressive world, and about the ways in which contemporary psychoanalytic discourse itself is and is not progressive.

Young-Bruehl

In her article, “Psychoanalysis and Social Democracy,” Elisabeth Young-Bruehl (2011[29]) constructs a narrative about the historical relations between psychoanalysis and post-WWII social democracy (with particular focus on the UK). Shaping this narrative is her view of the two most important post-war developments in left-wing psychoanalytic theory. The first is a realm of instinct theory that, she argues, Freud left under-theorised once having committed himself to the dual instinct theory of life and death: The ego-instincts, which include dependency needs, attachment needs, needs for love, care, and security. Post-war UK attachment theorists and British independents are the heroes of Young-Bruehl’s narrative, for they not only brought to the fore the importance of such needs, they also influenced social democratic policy. In so doing, these analysts contributed to what Young-Bruehl calls the general principle psychoanalysis and political progressives both came to champion: “Human beings cannot live well or happily in their families or communities or political arrangements unless these do not thwart their ego instincts” (p. 192).

The second psychoanalytic realm of theory to which Young-Bruehl draws attention is characterology, a field to which Freud contributed but which found its deepest elaborations in the work of left-wing analysts and theorists such as Reich, the Frankfurt School, and others concerned with problems of social inclusion and exclusion (problems that Young-Bruehl places under the umbrella term of “prejudice”). The neglect of the ego instincts again enters the narrative in her claim that Freudian characterologists were limited by a sole focus on sexual instincts. The post-war characterologists, on the other hand,

convinced post-war pragmatic socialists that they needed to focus their attention not just on class conflict and class struggle, but on all forms of social and political exclusion, as well as production of inequality – on all forms of prejudice considered as a social disease. Social democracy came to mean, in this sense, maximally inclusionary democracy, and the European social democrats designed programmes for bringing excluded peoples into citizenship and into the welfare states. (Young-Bruehl, 2011[29], p. 193)

Young-Bruehl goes on to discuss theorists who focus on dominant types of character within a society (for example, Adorno et al., 1950[1], and the authoritarian personality), as well as on the intergenerational transmission of dominant character types. Her narrative ends with the suggestion that the two realms, ego-instincts and characterology, need to be thought together. As she puts it, ego instinct theory tells you what humans need and characterology focusses politics on “equality and maximal inclusion of once-excluded groups, on human rights, and on political structures moving beyond nation-states and exclusionary sovereignty” (p. 194). Young-Bruehl’s own life work was in fact dedicated to the elucidation of different kinds of prejudices and the character types most closely associated with each kind. Her final work (2012[30]) took up a prejudice she felt she had overlooked in her earlier work (Young-Bruehl, 1996[28]), one closely connected to the thwarting of ego-instincts: the prejudice against children.

Alternate histories of modernity and subjectivity

Institutionalised individualisation

What strikes me about Young-Bruehl’s historiography is how different it is from two other stories about subjectivity and the politics of modernity that I had drawn on in a paper in which I had sought to understand why relational analytic theory has become a dominant psychoanalytic force in the US. In this paper (Layton, 2010a[21]), I looked at the socio-historic changes in subjectivity and intersubjectivity to which, I argued, relational analytic theory has been a response.

Many contemporary sociologists, for example, Beck (1999[2]), Beck and Beck-Gernsheim (2002[3]), and Giddens (1991[10]), have, with slightly different emphases, focussed their historiography of modernity and subjectivity in the West on the increasing disembedding from tradition of post-war subjects and the role played by experts in supporting the demand that subjects create themselves in the absence of socially sanctioned and agreed-upon traditions on which they might depend. Beck (1999[2]) characterised the post-WWII West as “second modernity,” a condition prominently characterised by the kinds of “risk” against which populations cannot insure themselves. Beck describes many of these risks as the “manufactured uncertainties” produced by first modernity (e.g., the threat of nuclear holocaust, environmental destruction). Beck and Beck-Gernsheim (2002[3]) use the term “institutionalised individualisation” to describe a historical, political and legal situation in which institutional structures are conceptualised around individual rights and duties and not around the interests of collectivities. Without recourse to tradition, and subject to a range of contradictory and ever-changing expert opinion, increasingly more people, they argue, are in the position of daily having to question how best to live their lives. The more enfranchised the segment of the population, the more options are available; but given the shift away from public responsibility for the welfare of populations that has taken place in many Western countries in the past 30 years, nearly everyone has found themselves left to find their way on their own. The condition of institutionalised individualisation in risk society means, on the subjective level, that more and more people can- and must- create what these theorists call “do-it-yourself biographies” that constantly teeter on the edge of becoming biographies of nervous and other forms of breakdown.

Theorists of institutionalised individualisation suggest that, in a world without traditional anchors, the only thing that anchors many of us is our intimate relationships. Giddens (1991[10]) speaks of the “pure relationship,” by which he means one not held together by any moral, religious, or social tradition but rather by whether or not the relationship meets the psychological needs of its participants. Individualisation means, then, for privileged individuals, an ability and a demand constantly to reflect upon whether or not a career or a relationship is making them happy, bringing personal fulfilment, and if not, whether or not they should stay in it. Beck-Gernsheim (2002[3], Ch. 5, n. 94, p. 80) cites as a prime example of this ethos the Fritz Perls motto that became so popular in the 60s:

I do my thing and you do your thing…I am not in this world to live up to your expectations, and you are not in this world to live up to mine. You are you and I am I; if by chance we find each other, it’s beautiful. If not, it can’t be helped.

The individualisation and risk society literature suggests different historical reasons from those on which Young-Bruehl relies to explain a shift in psychoanalytic theory regarding what lies at the heart of human motivation. Rather than positing, as she does, that psychoanalysts were crucial in recognising what humans need, these theories would likely suggest that the shift in psychoanalytic theory away from seeing sex and aggression as primary motivators of human desire toward, instead, seeing needs for safety and security as primary, is a function of living in an increasingly insecure world in which individuals have little to rely on besides their own psychic fortitude and, perhaps, intimate relations. This literature suggests that the ego instincts central to Young-Bruehl’s account might have become more important to tend to in the post-war period because, even in the welfare state, institutionalised individualisation proceeded apace – and because, as Giddens (1991[10]) suggests, late modernity is characterised by abstract systems that require of individuals a solid capacity for basic trust. Thus, if individuals are to thrive in these conditions, that is, avoid breakdown, they need to rely more on inner psychological resources than on the social surround. To develop basic trust, for example, attachment and other dependency needs must be attended to. In a world of risk, detraditionalisation, and contradictory expert knowledge claims, the capacity to depend on intimate relations crucially replaces the capacity to depend reliably on social holding environments. Thus, post-war social conditions that foster individualisation are progressive in some ways and in some ways not. One implication is that attending to attachment and dependency needs might not be the sine qua non of a progressive politics.

Governmentality

The governmentality literature is influenced by the work of Foucault on genealogies of subject positions and techniques of governance and normalisation (see, for example, Foucault, 1978[8], 1980[9]). As elaborated by Rose (1989[25]), one clear line in the history of western institutions from the 19th century on is an increasing demand for self-surveillance and self-control. Contrary to the individualisation theorists, Rose and others argue that normalisation techniques arose concurrently with industrialisation and urbanisation in order to maximise opportunity for the middle-class and minimise the threat to the middle-class of the poor and working class masses congregating in cities. Individualisation, according to Rose, means the production not just of individuals, but of knowable individuals.

In the Foucaultian paradigm, “the disciplines ‘make’ individuals by means of some rather simple technical procedures” (Rose, 1989[25], p. 135). Central to this paradigm are “regimes of visibility”: Where people gather en masse, they can be observed (e.g., in the school or the workplace, with the model being Jeremy Bentham’s 18th century design for penal institutions, the Panopticon). Regimes of visibility allow for institutions to operate according to a regulation of detail; a grid of codability of personal attributes emerges:

They act as norms, enabling the previously aleatory and unpredictable complexities of human conduct to be charted and judged in terms of conformity and deviation, to be coded and compared, ranked and measured (pp. 135-6).

The phenomenal world becomes normalised, “that is to say, thought in terms of its coincidences and differences from values deemed normal…” (Rose, 1989[25], p. 136).

Given this theoretical backdrop, Rose (1989[25]) finds, in the British welfare state, an increased social regulation of subjects. He argues that this was in no small measure accomplished by the intrusion of psychological and other experts into the private sphere practices of family life and the socialisation of children. Winnicott’s radio chats and childcare manuals come in for special censure, because, according to Rose, Winnicott’s discourse masterfully masked experts’ techniques of normalisation beneath a language about what is “natural” for a mother to feel and do. For example, Winnicott tells mothers that feeding is a natural act of love at the same time that he gives them advice about how to perform this natural act. Rose writes,

…on the one hand, in the attachment discourse, the family tie appears as ‘natural’; on the other parents can only carry out their task effectively when educated, supplemented, and in the last instance supplemented by psychologically trained professionals (Rose, 1989[25], p. 177).

For Rose, a mother’s desire for a hygienic home and healthy children, and parents’ conviction that love is essential to raising a normal child, are not natural convictions and desires but rather are socially produced in order to fit subjective desire with institutional requirements.

Comparing historiographies

In Rose’s argument, that “love” became thought of as the element that would produce normal children in the two decades after World War II, we find a historiography that is diametrically opposed to the ones offered by both the individualisation theorists and by Young-Bruehl. Where Beck, Beck-Gernsheim, and Giddens suggest that an increasing “disembedding from tradition” promotes individual autonomy and particular kinds of intimate relationships, Foucaultian theorists argue that experts and their expertise have become the new tradition. In this view, post-war subjects feel free and yet are increasingly regulated by regimes of what is considered to be “normal”:

The representations of motherhood, fatherhood, family life, and parental conduct generated by expertise were to infuse and shape the personal investments of individuals, the ways in which they formed, regulated and evaluated their lives, their actions, and their goals (Rose, 1989[25], p. 132).

In Young-Bruehl’s account, Winnicott and others in the independent psychoanalytic tradition developed their theory, practice, and public policy in response to the trauma, devastation, and abandonments of World Wars I and II. Rose, on the contrary, places Winnicott’s work in the context of a long history of expertise, the primary effect of which was to abet and normalise a self-regulation designed to bring the individual into harmony with the culture’s institutions – an effect Rose describes as “governing the soul.”

In suggesting that an important element in the history of Western modernity has been the kind of normalisation that supports prejudices, the governmentality literature challenges both Young-Bruehl’s thesis as well as her historiography. This literature raises several important questions: are the positions and practices that define the good and the healthy those that work in the service of regulating the poor or unruly, those that normalise and optimise middle-class opportunity? Are they practices that fit subjects for a certain kind of society, one in which alternative practices are pathologised? These questions perhaps challenge Young-Bruehl’s assertions that humans need a certain kind of care to thrive and to be more resistant to prejudices. But Rose skirts the question central to Young-Bruehl’s project: Are there basic human needs that must be met for a democratic society to exist? If so, is there an important role for psychoanalysts to play in policy formation? Are psychoanalysts doomed simply to be lackeys of state and corporate power or might they offer a counter-discourse to contemporary social and political discourses?

Staking a claim

I write and think in a relational analytic tradition that is very much influenced by both the Budapest psychoanalytic school of Ferenczi and Balint and the British Independent tradition on which Young-Bruehl bases her analysis. Yet, at the same time, my work differs from Young-Bruehl’s, particularly in our understandings of social character. In this domain, I have been more influenced by the Frankfurt School and its heirs than by Freudian notions of character. From the 80s on, I have written, for example, about the relation between capitalism and narcissistic personality. Much of my work is related directly to the clinic and focusses on how the normalising practices of both the psychoanalytic field and of class, race, sex, and gender identity production are replicated in unconscious collusions between patient and therapist (Layton, 2002[13], 2006a[16], 2007[18], 2008[19], 2009[20]) – replications that I have referred to as normative unconscious processes. But, like Young-Bruehl, I also assume in my work that humans need reliable caretaking to thrive and to be able to negotiate among their dependency needs, needs for self-assertion, and needs for recognition. In different ways, both the individualisation literature and the governmentality literature suggest that such negotiations are not basic to being human but are rather a product of a particular historical formation. For example, as the Foucaultian tradition moves into researching post-welfare state subjectivities, we find arguments about how subjects now have to wrestle with the demands of neoliberalism. Binkley (2009[4]) argues that in order to produce the “enterprising” selves necessary to function in a world in which responsibilities for the population’s welfare have shifted from the public sphere onto the individual, people have to disidentify with the practices that had made them comfortable with dependency on the state (and dependency in general) and identify instead with practices that enable them to thrive in neoliberal free market and socio-political conditions. Looking at self-help books, the field of coaching, and positive psychology, Binkley (2011a[5], b[6]) persuasively identifies some of the practices that experts encourage people to adopt – and most of them work in the service of demonising dependency and interdependence.

While I find this work quite valuable, I think about these same phenomena somewhat differently. In my view, agentic strivings and strivings for connection are likely universal and basic to being human, but I believe such strivings are negotiated quite differently depending on prevailing norms for what a “proper” human in a particular time and place needs to do to get love, social recognition, and a sense of belonging.

From my 1990’s papers on gender to recent papers on neoliberal subjectivities (Layton, 2009[20], 2010b[22]), central to my work has been the effects of the cultural repudiation of what Young-Bruehl includes under ego instincts (most of which have been historically associated with femininity). I concur with Young-Bruehl that the classical psychoanalytic literature and the ego-psychological literature that was dominant in the US until recently generally valued most highly an autonomy based in separation from the other and denial of or overcoming of dependence.

This way of conceptualising an autonomy that splits off attachment needs connects quite directly with characterology, and so, like Young-Bruehl, I believe that the thwarting of “ego instincts” does indeed produce certain kinds of character. But, unlike Young-Bruehl’s version of characterology, which is rooted in Freudian character types and the defences particular to each type, I focus on the way character is formed by socio-historical conditions of inequality and the intergenerational transmission of the effects of inequality. More particularly, character, in my view, emerges in part from the social possibilities for negotiating autonomy and dependence that are available and/or denied to particular social groups, and with the way that inequalities of race, gender, class, sexuality inform practices that inflict humiliations and other psychological damage. In any culture or subculture, some ways of being and acting are recognised as “proper” by the social groups and families to which one wants to belong and be loved by, and some “improper.” What is unrecognised or felt to be improper is often split off. Disavowed “not-me” states have to be repeatedly defended against in identity performances and relational enactments that affirm the norm that caused psychic pain in the first place. Various kinds of character – or versions of subjectivity – or versions of living dependency and autonomy – are produced and sustained by these unconscious repetitions that I refer to as normative unconscious processes (Layton 2004a[14], 2006a[16], 2007[18]).

An example: In my early work on gender (Layton, 1998/2004[12]), I argued that the dominant ideals and ideologies of masculinity and femininity in the post-war US bred two subtypes of narcissism, each marked by cultural demands to split off some part of what it is to be human. Heterosexual masculinity, I argued (along with many other feminists), was marked by a self-centred version of autonomy produced by a denial of attachment needs and other ego instincts discussed above. The ideal of femininity was marked by a repudiation of autonomous strivings which often led, in practice, to hostile versions of dependency and severe conflicts over self-assertion. Different groups are subject to different forms of narcissistic wounding, but what gets split off and either dissociated or, as a Freudian might see it, repressed, are human needs and capacities, and character issues emerge when, for example, a man comes to feel that he cannot be both masculine and dependent. In my version of characterology, the narcissistic wounds suffered, for example, in conforming to socially and historically specific ideals of masculinity produce particular defences and ways of relating (transferences and counter-transferences) that become normative. Each social group’s ways of defending against its wounds tend to inflict wounds on other groups – and these processes of mutual wounding need to be studied always with reference to the particular power arrangements within which they unfold.

In more recent work (Layton, 2009[20], 2010b[22]), I, too, have tried to historicise what seems to me to be, since the Reagan and Thatcher era, an increasing general revulsion toward dependence and vulnerability. Before being conscious of “neoliberalism” as a form of governmentality, I wrote, for example, about the way that television shows of the 90s were normalising for middle-class women the same counter-dependent norms for subject formation that had until then prevailed for middle-class men (Layton, 2004b[15]) – again producing a particular kind of social character with particular psychosocial defences. When dependence and interdependence are repudiated and made shameful, as they have been in the neoliberal US – where the attack on the poor and vulnerable continues unabated, where social policies tear away at the containment and care offered by the welfare state, and where income inequality is at or close to historic highs – you find characteristic narcissistic defences against trauma: retaliation and withdrawal, oscillations between grandiosity and self-deprecation, devaluation and idealisation, denials of difference and the rigid drawing of boundaries between who is “in” and who is “out” (Layton, 2006b[17], 2009[20], 2010b[22]).

Psychoanalysis and progressive politics

In “normalising” dependency and interdependence as part of what it means to be human, and in critiquing versions of autonomy that deny an embeddedness in relation, contemporary psychoanalytic theory (particularly relational analytic theory and all those theories indebted to the Hungarian and British Independent traditions lauded by Young-Bruehl) offers something of a counter-discourse to hegemonic neoliberal discourses. All of the psychoanalytic theories of which I am aware certainly counter what Binkley describes as the versions of subjectivity promoted in neoliberal discourses, that is, theories and practices that have no use for looking within for understanding suffering, for thinking about an individual’s problems in the context of relationships, or for any notion of unconscious process that divides the self against the self. Where psychoanalysis certainly falls short, however, is in its continued separation of the psychic from the social, its general refusal to understand what people suffer from as having something to do with societal conditions. So I do believe in the importance of Young-Bruehl’s project to question and think historically about what psychoanalytic theories promote as the good. I do not think that the practices promoted by psychoanalysis are inherently democratic, precisely because of the way the social is dissociated from conceptualisations of subjectivity.

One effect of the way psychoanalysis separates the psychic and the social is that psychoanalysts today, in the US at least, have little impact on public policy. But the marginalisation of psychoanalysis is not the fault of psychoanalytic theory alone: It is also in no small measure due to the dominance of neoliberal discourses. Perhaps precisely because psychoanalysis has lost its hegemony and become a minority discourse, we find current trends in psychoanalysis that do connect with progressive politics, trends that likely also grew out of the progressive politics of the 60s, a time in which many of our current theorists came of age. Among these trends, I would include the radical questioning and re-thinking of the authority of the analyst and the awareness of the effect of the analyst’s unconscious on treatments (e.g., Mitchell, 1997[24]; Hoffman, 1998[11]); re-formulations of theory that acknowledge the power inequities inherent in many social norms and that thus work to challenge power and depathologise non-normative ways of being; and a commitment, in some quarters at least, to think about the ways that politics enter the clinic (Samuels, 2001[26]; Layton et al., 2006[23]).

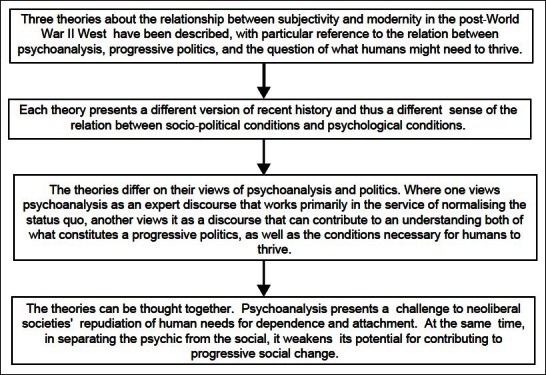

Concluding Remarks [See also Figure 1: Flowchart of paper]

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Paper

To summarise, on the one hand, in my work I draw on many psychoanalytic theorists who talk about tending to what Young-Bruehl calls “ego-instincts”: Bion on containment, Winnicott on holding. And on the other, I focus on defences like splitting and projection that arise from failures in containment and holding. As Young-Bruehl might suggest, this is where a kind of characterology comes in. But unlike the version of characterology she favours, I look at character formation more relationally. I ask if there are particular patterns of defences, particular kinds of repetition compulsions, transferences and counter-transferences that arise in relation to particular power arrangements, policies, cultural trends and discourses. More broadly, I try to understand denials of the ways in which in-groups and out-groups are related, and the sado-masochis tic forms of power struggle that often result from such denials (see also Scanlon and Adlam, 2008[27]). Psychoanalysis is thus, for me, necessary to understand what might be essential to achieving a progressive democratic politics in which humans might thrive.

At the same time, drawing on the governmentality and individualisation literatures, I also think about ways that therapists might unconsciously collude in sustaining neoliberal practices that favour performance and achievement over comfort with dependence, or that favour a kind of care of the self that disregards care for the collective good (Layton 2006b[17], 2007[18], 2009[20], 2010b[22]). Here, I see psychoanalysis as at times contributing to anti-democratic and anti-human practices. Thus, I understand psychoanalysis to be a culturally embedded discourse and practice that cannot be characterised as either uniformly democratic or anti-democratic. Rather, to be able to assess what is progressive, we have to understand each version of psychoanalytic theory in its particular historical context, and interrogate both a theory’s assumptions as well as the socio-cultural uses to which it is put.

Take home message

Although the theorists I discuss in this paper conceptualise the relation between modernity and subjectivity quite differently, they, and I, agree that social, political, and cultural institutions tend to produce versions of subjectivity characteristic of their time and place.

Human needs for assertion, connection, and recognition might well be universal, but it is important to understand how needs are negotiated differently in different socio-historical conditions.

Although psychoanalytic theory colludes with the dominant Western cultural practice of separating the psychic from the social, it yet offers a counter-discourse to what has been neoliberalism’s characteristic repudiation of dependency needs and denial of mutual interdependence.

Questions that the Paper Raises

How do we understand differing accounts of the relation between the history of modernity and changes in subjectivity?

Is there anything universal about being human, and if so, how do we understand the relation between the universal and the historically situated?

Is psychoanalysis a progressive and democratic discourse?

What are some of the psychic effects of neoliberal discourses and where does psychoanalysis stand in relation to these discourses?

About the Author

Lynne Layton, Ph.D. is Assistant Clinical Professor of Psychology, Harvard Medical School. She has taught courses on women and popular culture and on culture and psychoanalysis for Harvard’s Committee on Degrees in Women’s Studies and Committee on Degrees in Social Studies. Currently, she teaches and supervises at the Massachusetts Institute for Psychoanalysis and supervises at the Boston Institute for Psychotherapy. She is the author of Who’s That Girl? Who’s That Boy? Clinical Practice Meets Postmodern Gender Theory (Routledge, 2004), co-editor, with Susan Fairfield and Carolyn Stack, of Bringing the Plague. Toward a Postmodern Psychoanalysis (Other Press, 2002), and co-editor, with Nancy Caro Hollander and Susan Gutwill of Psychoanalysis, Class and Politics: Encounters in the Clinical Setting (Routledge, 2006). She is co-editor of the journal Psychoanalysis, Culture and Society [http://www.palgrave-journals.com/pcs/index.html] and associate editor of Studies in Gender and Sexuality [http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/hsgs20/current]. Her private practice is in Brookline, Ma.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: I have received no funding or sponsorship by an agency for the work reported in this paper.

Declaration

This is my own original unpublished work, not submitted for publication elsewhere.

CITATION: Layton L. Psychoanalysis And Politics: Historicising Subjectivity. Mens Sana Monogr 2013;11:68-81.

Peer Reviewers for this paper: Steven Botticelli PhD; Janice Haaken PhD

References

- 1.Adorno TW, Frenkel-Brunswik E, Levinson DJ, Sanford RN. The Authoritarian Personality. New York: Norton; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck U. World Risk Society. London: Polity; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck U, Beck-Gernsheim E. Institutionalized Individualism and its Social and Political Consequences. London: Sage; 2002. Individualization. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binkley S. The work of neoliberal governmentality: Temporality and ethical substance in the Tale of Two Dads. Foucault Stud. 2009;6:60–78. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binkley S. Happiness and the program of neoliberal governmentality. Subjectivity. 2011a;4:371–94. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binkley S. Psychological life as enterprise: Social practice and the government of neoliberal interiority. J Hist Hum Sci. 2011b;24:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- 7.du Gay P. Against ‘Enterprise’ (but not against ‘enterprise’, for that would make no sense) Organization. 2004;11:37–57. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foucault M. In: Discipline and Punish. Sheridan A., editor. New York: Pantheon; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foucault M. In: The History of Sexuality. Hurley R, editor. Vol. 1. New York: Vintage; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giddens A. Modernity and Self-Identity. Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman I.Z. Ritual and Spontaneity in the Psychoanalytic Process. New York: Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Layton L. Who’s that Girl. Who’s that Boy? Clinical Practice Meets Postmodern Gender Theory. New York: Routledge; 1998/2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Layton L. Cultural hierarchies, splitting, and the heterosexist unconscious. In: Fairfield S, Layton L, Stack C, editors. Bringing the Plague. Toward a Postmodern Psychoanalysis. NY: Other Press; 2002. pp. 195–223. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Layton L. That place gives me the heebie jeebies. Int J Crit Psychol. 2004a;10:51–64. In: Layton L, Hollander NC, Gutwill S, editors. Psychoanalysis, Class and Politics: Encounters in the Clinical Setting. London: Routledge; 2006. p. 51-64. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Layton L. Working nine to nine: the new women of prime-time. Stud Gend Sex. 2004b;5:351–69. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Layton L. Racial identities, racial enactments, and normative unconscious processes. Psychoanal Q. 2006a;LXXV:237–69. doi: 10.1002/j.2167-4086.2006.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Layton L. Retaliatory discourse: the politics of attack and withdrawal. Int J Appl Psychoanal Stud. 2006b;3:143–55. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Layton L. What psychoanalysis, culture and society mean to me. Mens Sana Monogr. 2007;5:146–57. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.32159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Layton L. Relational thinking: from culture to couch and couch to culture. In: Clarke S, Hahn H, Hoggett P, editors. Object Relations and Social Relations. London: Karnac; 2008. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Layton L. Who’s responsible. Our mutual implication in each other’s suffering? Psychoanal Dialogues. 2009;19:105–20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Layton L. Dialectical constructivism in historical context: expertise and the subject of late modernity. Paper presented at meetings of Division, American Psychological Association, Chicago. 2010a [Google Scholar]

- 22.Layton L. Irrational exuberance: neoliberal subjectivity and the perversion of truth. Subjectivity. 2010b;3:303–22. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Layton L, Hollander NC, Gutwill S, editors. Psychoanalysis, Class and Politics: Encounters in the Clinical Settting. New York: Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell SA. Influence and Autonomy in Psychoanalysis. New York: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rose N. Governing the Soul. The Shaping of the Private Self. London: Free Association Books; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samuels A. Politics on the Couch. London: Karnac; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scanlon C, Adlam J. Refusal, social exclusion and the cycle of rejection: A cynical analysis? Crit Soc Pol. 2008;28:529–49. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young-Bruehl E. The Anatomy of Prejudices. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young-Bruehl E. Psychoanalysis and social democracy: A tale of two developments. Contemp Psychoanal. 2011;47:179–203. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young-Bruehl E. Childism. New Haven: Yale University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]