Abstract

It is important that every citizen knows the law of the state. Psychiatry and law both deal with human behaviour. This paper attempts to highlight the interplay between these two by discussing about various legislations like The Family Courts Act 1984, Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act 1985, Juvenile Justice Act 1986, Consumer Protection Act 1986, Persons with Disability Act 1995, The Maintenance and Welfare of Senior Citizens Act 2007.

Keywords: Aruna Shanbaug case, Attempt to Suicide: Section 309 Indian Penal Code, Bolam principle, Consumer Protection Act 1986, Family Courts Act 1984, Juvenile Justice Act 1986, Maintenance and Welfare of Senior Citizens Act 2007, Mens Rea, Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act 1985, Persons with Disabilities Act 1995

Introduction and Tributes

I am deeply humbled as I stand here to give my Presidential Address. I would foremost like to thank my teachers, colleagues and family because of whose encouragement and support I stand here today.

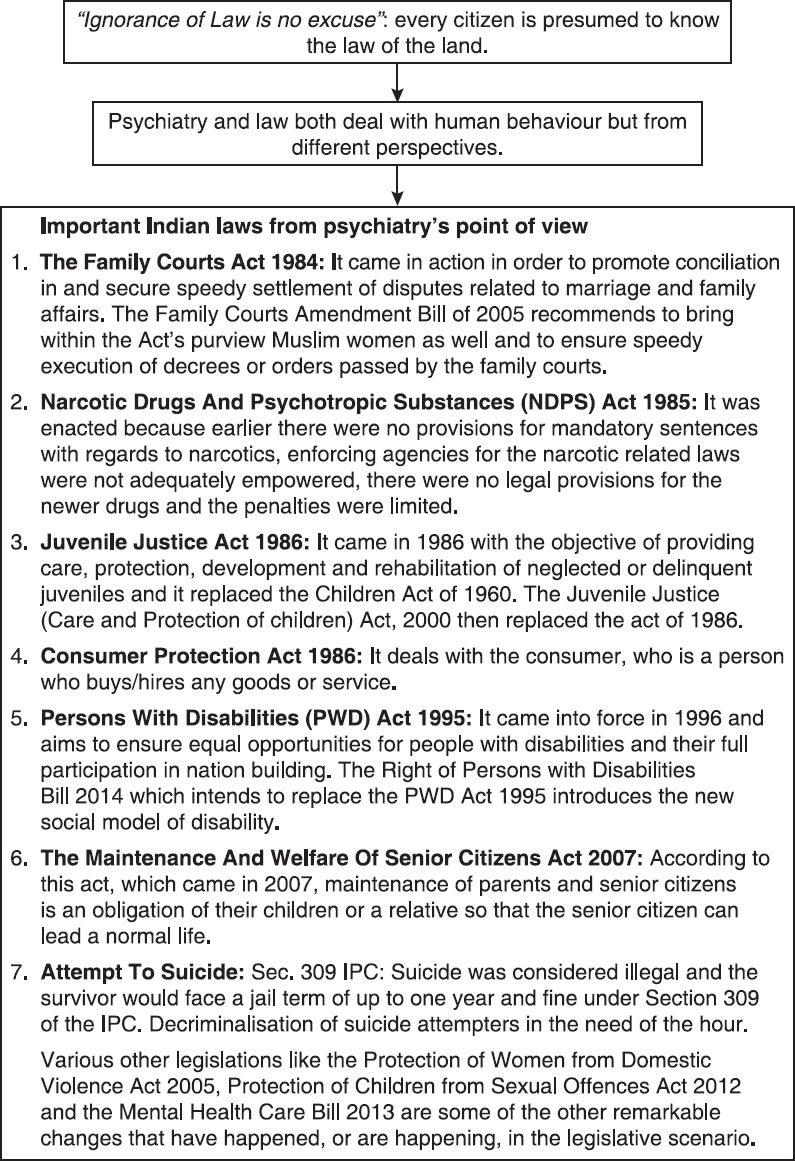

‘Ignorance of Law is no excuse’, is the principle in jurisprudence. This means every citizen is presumed to know the law of the land. Psychiatry and law both deal with human behaviour but from different perspectives. Psychiatry deals with human behaviour and law deals with the control of human behaviour. It will be my attempt to create awareness of their interplay through this Address. The Mental Health Act has not been included in this Address because it has been talked about and discussed a lot at various forums.

(Note added in 2015: Along with the facts and details mentioned at the Presidential Address in 1998, a mention in this article has also been made of the important developments that have occurred in legislations after 1998 till date.)

The Family Courts Act 1984

The Family Courts Act of 1984 (The Family Courts Act, 1984[6]) came in action in order to promote conciliation in and secure speedy settlement of disputes related to marriage and family affairs. The various matters under its jurisdiction were validity and nullity of marriage, divorce, maintenance, custody of children, property, adoption, etc. It provided for establishing a family court for every area of a state such as a town or city which had a population of >1 million. According to the Act the various proceedings under this Act were to be carried out in camera in order to maintain confidentiality. It provided for counsellors for reconciliation in the family court, associations with social welfare agencies, free legal aid for weaker sections and assistance of legal experts if required.

Laws have always been complicated whenever it comes to mental illness in one of the spouses as a reason for seeking divorce. In this regard two elements are necessary for a person to seek divorce, that is, the spouse should have an unsound mind or mental disorder and the disease must be of such a kind and of such an extent that the other party cannot be reasonably expected to live with the spouse having the mental illness. An amendment to this Act came in 1991.

The Family Courts Amendment Bill of 2005 recommends to bring within the Act’s purview Muslim women as well and to ensure speedy execution of decrees or orders passed by the family courts. The local Civil and Criminal courts are conferred the jurisdiction to execute the orders and decrees of family courts.

Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act 1985

The Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act 1985 (NDPS Act, 1985[10]) was enacted because earlier there were no provisions for mandatory sentences with regards to narcotics, enforcing agencies for the narcotic related laws were not adequately empowered, there were no legal provisions for the newer drugs and the penalties were limited. The NDPS Act 1985 consolidated and amended the then existing laws related to narcotics. There have been 4 amendments to the act, in 1988, 2001, 2011 and 2014. Also, the prevention of Illicit Trafficking in NDPS Act was passed in 1988 to enable implementation and enforcement of NDPS 1985. According to the NDPS Act, Mens Rea is presumed under Section 35. (Mens Rea is the intent of committing the offence; it is one of the necessary elements of the crime in law. It is the mental element of an offence, the awareness of a person that his or her conduct is criminal). In accordance with international conventions, it deals with control and regulation of NDPS, and the establishment of special courts for the enactment and rigorous imprisonment of offenders. Moreover, the offences are regarded as non-bailable and cognisable. Also, the court can release certain offenders on probation for undergoing medical treatment and to furnish a medical report within a year (Section 39). Immunity from prosecution is given to addicts volunteering for treatment once in a lifetime (Section 64A) and the government is expected to establish centres for their identification, treatment, education, after care and rehabilitation.

In the most recent amendment in 2014 (The NDPS [Amendment] Act, 2014[11]) a new category of ‘essential narcotic drugs’ has been added which will promote the medical and scientific use of NDPS in addition to containing the illicit use under this Act. In addition the amendment also reflects the principle of balance between control and availability of narcotic drugs; it allows for management of drug dependence and authorises the government to recognise and approve treatment centres. It also introduces some changes with regards to penal sentencing. However as an increasing number of countries all over the world have been slowly moving towards decriminalisation of possession and drug use, the fact that consumption of drugs is still considered punishable seems to be against the current international drug policy.

Juvenile Justice Act 1986

The Juvenile Justice Act came in 1986 (The Juvenile Justice Act, 1986[7]) with the objective of providing care, protection, development and rehabilitation of neglected or delinquent juveniles and it replaced the Children Act of 1960. According to the Act, males below the age of 16 years and females below the age of 18 years were considered as juvenile. It was considered that a child under 7 years could not commit an offence and a child between 7 and 12 years could not commit an offence if he has not attained sufficient maturity of understanding to judge the nature and consequence of the act. It was enacted to ensure that there was uniformity in the law of various states and that no juvenile was confined to jails. It dealt with 3 types of children namely: delinquent, neglected and uncontrollable. It laid down provisions for juvenile courts, juvenile welfare boards, probationary officers, psychologists and psychiatrists in dealing with juvenile offenders.

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2000[8] then replaced the act of 1986 after India signed the UN Convention on Rights of the Child in 1992. There have been further two amendments of the act in 2006 and 2011.

Consumer Protection Act 1986

The Consumer Protection Act of 1986 (The Consumer Protection Act of 1986[5]) deals with the consumer, who is a person who buys/hires any goods or service. Included within the definition on the word ‘Service’ under this Act is the service rendered by doctors, hospitals and nursing homes. In a doctor-patient relationship, the patient is entitled to services from the doctor in such a degree of professional skill and expertise as would be expected from a medical man of similar qualification and standard. The standard of duty is laid down on the basis of the Bolam Principle (Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee, 1957[1]) which says that, management of a patient is to be in accordance with a practice accepted at the time as proper by two different responsible groups of medical opinion of the same speciality. Among the ten reliefs the ones applicable to medical profession are to remove the defects and deficiencies, to pay such amount as compensation for any loss or injury suffered by consumer due to negligence of opposite party and to provide for adequate costs to the parties.

Persons with Disabilities Act 1995

According to the 2001 Census there were about 2.2 crore persons with disabilities (PWD) in India, constituting almost 2.1% of the total population. The estimated population of PWD in 2008 was 2.44 crores. The Economic and Social Communication for Asia and Pacific had declared the period of 1993-2002 as the Asian and Pacific decade of the disabled. India being a signatory to this proclamation started the process for drafting and enacting specific legislations that ensured equal opportunities and full participation and protected the rights of people with disabilities. Drafting of the PWD Act was led primarily by PWD themselves, along with many like-minded professionals. The Act (The PWD Act, 1995),[13] which came into force in 1996, aims to ensure equal opportunities for people with disabilities and their full participation in nation building. The Act provides for the prevention and early detection of disabilities, and also education, employment, non-discrimination, research and manpower development, affirmative action, social security and grievance redressal for persons with disability. The beneficiaries of this act are people with blindness, low vision, cured leprosy, hearing impairment, locomotor disability, mental retardation and mental illness.

India, having ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) (Convention on Rights of PWD[2]) is obligated to enact suitable legislation in furtherance of rights recognised in UNCRPD. As per the UNCRPD, persons with disability are right holders instead of passive recipients of government schemes. The PWD Act 1995 had not expressly recognised rights, but also laid emphasis on the need to eliminate physical and social barriers so as to promote the participation of people living with disabilities. The Right of PWD Bill 2014 (The Right of PWD Bill 2014[14]), which intends to replace the PWD Act 1995 introduces the new social model of disability. The highlights of the new proposed bill are that it provides for 5% reservation in jobs, ensures political participation, says that any person who is unable to vote in person due to disability is entitled to opt for postal ballot, allows mentally unsound women the right to fertility and prescribes punishment for forced abortion or hysterectomy on them. The number of disabilities included in the Act has increased.

The National Trust for welfare of persons with autism, cerebral palsy, mental retardation and multiple disabilities Act 1999 (The National Trust Act 1999[12]) strengthened the facilities to provide support to persons with disability to live as independently as possible, to live within their own families, to deal with problems of persons with disability who do not have family support, to promote measures for the care and protection of persons with disability in case of event of death of parents or guardians and also lays down the procedure for appointment of guardians and trustees for persons with disability requiring protection.

The Maintenance and Welfare of Senior Citizens Act 2007

According to this Act, which came in 2007, maintenance of parents and senior citizens is an obligation of their children or a relative so that the senior citizen can lead a normal life (The Maintenance and Welfare of Senior Citizens Act 2007[9]). It also provides for the establishment of old age homes, provisions for medical care, protection of life and property of senior citizens, defines offences and lays down procedures for trials. This Act provides for a maximum maintenance of INR 10,000/- for senior citizens and abandoning is fined with INR 5000/-, or 3 months imprisonment, or both.

Attempt to Suicide: Section 309 Indian Penal Code – Law, Claw or Flaw?

Suicide was considered illegal, and the survivor would face a jail term of up to 1-year and fine under Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). It was the only section in the IPC where an attempt was punishable, but a completion could not be punished. Decriminalisation of suicide attempters in the need of the hour. It was long argued by professionals from various fields that Section 309 of penal code be effaced from the statute book in order to humanise our penal laws (Kamath, 1998).[3] It was regarded as a cruel and irrational provision, which may result in punishing a person doubly, that is, punishing a person who would already be undergoing ignominy because the attempt to commit suicide had failed. Accordingly the Supreme Court attempted to decriminalise suicide in 1994; however it was restored 2 years later. The present government’s decision of bringing in decriminalisation of suicide is in keeping with both humanisation as well as globalisation. Also, the Mental Health Care Bill supports the removal of Section 309.

One of the landmark cases in the debate regarding euthanasia is the Aruna Shanbaug case. A noted social activist had filed a writ petition in 2009 in the Supreme Court of India for mercy killing on behalf of the petitioner. A landmark judgment was passed by Supreme Court in 2011, which said that a decision had to be taken to discontinue life support either by the parents, or the spouse, or other close relatives, or by a next friend, or by the doctors attending to the patient, in the best interest of the patient. Such a decision however required approval from the High Court concerned. When such an application is filed, the Chief Justice of the High Court should forthwith constitute a Bench of at least two Judges who should decide to grant approval or not. A committee of three reputed doctors was to be nominated by the Bench, who would give a report regarding the condition of the patient. Before giving the verdict a notice regarding the report should be given to the close relatives and the State. After hearing the parties, the High Court could give its verdict. This judgment, having legalized non-voluntary passive euthanasia and having included a psychiatrist in the board of doctors for clinical assessment, has entrusted a huge responsibility to the psychiatrists (Rautroy, 2011).[4] This judgement and various other legislations like the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act 2005, Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act 2012 and the Mental Health Care Bill 2013 are some of the other remarkable changes that have happened, or are happening, in the legislative scenario.

Concluding Remarks

It is important for psychiatrists and other mental health workers to know about these legislations as well as about the others such as the Mental Health Act, which have not been discussed here. For example, in case of the POCSO Act, it is important for mental health workers to know about the Act so that they know the reporting procedures so as to help their patients, as well as to know the fact that it is necessary for mental health workers to report such cases whenever they come across them, failing which they can be subjected to punishment. Though there are a few areas, which are yet untouched and need to be worked upon, these legislations, as and when they have been enacted, have definitely helped us take a step forward [Figure 1: Flowchart of paper].

Figure 1.

Flowchart of paper

Take Home Message

It is important for each and every citizen to be aware of the laws of the state. Ignorance is no excuse. There are many laws which are important in the practice of Psychiatry and hence it is important for mental health professionals to be fully aware of them [Figure 1: Flowchart of paper, especially last item].

Questions that this Paper Raises

As mental health professionals how important is law to us?

Even though we say these legislations have helped us take a step forward, is it really so?

What does the fact that there has been a need for enacting legislations such as those for maintenance of senior citizens or for protection of children really suggest?

Do we need more laws or should we be looking for a society that can flourish ‘law free’?

About the Author

Ravindra Kamath MD is currently the Professor and Head, Department of Psychiatry at T. N. Medical College and B. Y. L. Nair Ch. Hospital, Mumbai, India. He has an additional qualification in law and Forensic Psychiatry is his field of special interest. He was former visiting professor at the New Law College. He was former President of Bombay Psychiatric Society and former chairperson of CME Committee, IPS. He has authored several national and international publications and was also actively involved in International Research work in the process of informed consent.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Surbhi C. Tivedi, Senior Resident, Department of Psychiatry, T. N. Medical College and B. Y. L. Nair Ch. Hospital for her help in compiling the article.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Declaration

This is my original unpublished work and it has not been submitted for publication elsewhere.

CITATION: Kamath RM. Psychiatry and law: Past, present and future. Mens Sana Monogr 2015;13:105-113.

Peer reviewer for this paper: Anon

References

- 1.Bolam v. Friern Hospital Management Committee. 1957. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 23]. 1 WLR 582. Full Act. Available from: http://www.oxcheps.new.ox.ac.uk/casebook/Resources/BOLAMV_1%20DOC.pdf . Available from: http://www.e-lawresources.co.uk/Bolam-v–Friern-Hospital-Management-Committee.php .

- 2.Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The United Nations. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 23]. Available from: http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml .

- 3.Kamath R. Attempt to commit suicide sec. 309 (Indian Penal Code) – Law, claw or flaw. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:75. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rautroy S. Passive mercy euthanasia with limits. The Telegraph 8th March. 2011. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 23]. Available from: http://www.telegraphindia.com/archives/archive.html .

- 5.The Consumer Protection Act of 1986, Act No. 68 of 1986. Bare Act. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 23]. Available from: http://www.ncdrc.nic.in/1_1.html .

- 6.The Family Courts Act, 1984: Act No. 66 of 1984. The Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Part IISection I; Ministry of Law, Justice and Company Affairs (Legislative Department) [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 23]. Available from: http://www.vakilno1.com/bareacts/familycourtsact1984/familycourtsact1984.html .

- 7.The Juvenile Justice Act, 1986: Act No. 53 of 1986. Bare Act. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 23]. Available from: http://www.icf.indianrailways.gov.in/uploads/files/THE%20JUVENILE%20JUSTICE%20ACT.pdf .

- 8.The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of children) Act, 2000: Act No. 12 of 2011. Bare Act. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.nls.ac.in/ccl/jjdocuments/mahjj.pdf .

- 9.The Maintenance and Welfare of Senior Citizens Act 2007, Act No. 56 of 2007. Bare Act. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 23]. Available from: http://www.dc-siwan.bih.nic.in/senior_citizens_act.pdf .

- 10.The Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985: Act No. 61 of 1985. The Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Part II-Section I; Ministry of Law and Justice (Legislative Department) [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 23]. Available from: http://www.icf.indianrailways.gov.in/uploads/files/Narcotic%20drugs.pdf .

- 11.The Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (Amendment) Act, 2014: Act No. 16 of 2014. The Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Part II-Section I; Ministry of Law and Justice (Legislative Department) [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 23]. Available from: http://www.indiacode.nic.in/acts2014/16%20of%202014.pdf .

- 12.The National trust for welfare of persons with autism, cerebral palsy, mental retardation and multiple disabilities Act 1999, Act No. 44 0f 1999. Bare Act. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 23]. Available from: http://www.lawyersclubindia.com/bare_acts/National-Trust-for-Welfare-of-Persons-with-Autism-Cerebral-Palsy-Mental-Retardation-and-Multiple-Disabilities-Act-723.asp .

- 13.The Persons with Disabilities Act, 1995: Act No. 1 of 1996. The Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Part II-Section I; Ministry of Law, Justice and Company Affairs (Legislative Department) [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 23]. Available from: http://www.vikaspedia.in/social-welfare/differently-abled-welfare/disabilitiesrules1996 .

- 14.The Right of Persons with Disabilities Bill. 2014. [Last accessed on 2015 Feb 23]. Available from: http://www.prsindia.org/billtrack/the-right-of-persons-with-disabilities-bill-2014-3122 .