Abstract

In this commentary on the article, “The Task Before Psychiatry Today Redux: STSPIR,” (Singh, 2014)[20], the author, while agreeing with most of the paper’s findings, proposes a rather parallel judgment that intersects at the same paths ahead. There is a need for widespread and easily available essential mental health services in India. Health agenda must focus on spreading and scaling up psychiatric services. There is also a need to spread awareness of psychiatry and mental health and, as a psychiatrist, one must focus on making psychiatry available to a wider audience. Psychiatrists need to maintain a holistic view of psychiatric disorders while viewing them from both a neurobiological and psychosocial perspective. There is a need to revamp psychiatric training in departments with an increase in the thrust toward fostering translational research excellence in various spheres. Psychiatrists must continue to be trained in psychotherapy and practice it regularly. Psychiatric departments need to promote research excellence and focus on reducing brain drain. The practical applications of the tasks set out for psychiatry are more difficult than one can imagine, and a conscientious effort in that direction shall serve for its betterment. The future is bright and psychiatry must work toward making it brighter.

Keywords: Anti-psychiatry, Brain drain, Disaster psychiatry, Discrimination, Future of psychiatry, Health agenda, Integration of approaches, Psychiatric departments, Psychiatric patients, Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, Research excellence, Scale up services

Introduction

The article written by Singh (2014)[20] on the task before psychiatry today speaks with great elaboration on the goals this field needs to set and achieve in the next two decades. It is rather broad in its outlook, and achieving the goals set in the paper will need one to surmount huge barriers and cross mighty chasms. I am writing this commentary with the view that though I agree with the outline that the author has proposed, I hold a rather less magnanimous view of the path he has set. While I agree with most perspectives put forth, there are some albeit minor disagreements; or, rather, to put it differently, intersecting views, which on execution would meet the same goals further down the path. I shall, moreover, focus on the path psychiatry and psychiatrists need to take in India.

Increasing Psychiatric Services in India

I totally agree with the view that we need to scale up services in psychiatry but this needs the help and liaison of both the government and private sectors. Private hospitals, for example, need to be more accommodative in their view toward psychiatry and must be ready to scale up their own psychiatric setups. While many private hospitals have huge cardiology and nephrology units, they have miniscule or virtually nonexisting psychiatry units. It pains me when huge private centers have regular camps on cardiac and health checkups, including knee replacements, which is no doubt revenue generating to the center, but proposals to have a mental health checkup camp are met with a curt refusal. I am often told that we are a prime private hospital and do not want to project ourselves as a psychiatric (read mental) hospital.

A way to upscale mental health (or, for that matter, any health service) is public–private partnerships (PPP). PPP is like a good marriage where neither party suffers or compromises and can bring about growth of both at the expense of neither. Private partners not looking for their own financial benefits need to partner with municipal and government centers as well as provide help to government medical college departments forming memorandum of understanding that could go a long way to provide increased workforce and expertise to these centers, allowing them to grow and at the same time helping society at large as a part of their social responsibility (Nishtar, 2004[13]; Richter, 2004[17], and Collins et al., 2011[4]). This will result in all sections of society getting good mental health care with similar parameters and help in scaling up mental health services in a graded, judicious, and uniform manner.

Neglect of Psychiatric Disorders in Health Planning

Mental health and mental illness have borne the brunt of negative portrayal through the ages. There is no separate budget for mental health in India. Nothing is done even for the mental health of medical professionals. Doctors deal with so much stress day in and day out but do very little to enhance their own mental health. Divorce rates and family issues are highest in medical professionals as well as rates of both physical illnesses and depression (Shanafelt et al., 2013[18]). Yet medical professionals retain their cynicism toward their psychiatrist counterparts. There is no mental health body which looks into community mental health from a government perspective, and the need for community mental health initiatives from the Indian government leaves much to be desired. Even the World Health Organization speaks of depression being the second most common cause of morbidity worldwide but does not encourage funding to governments to reduce the same (World Health Organization, 2001[23], Lépine and Briley, 2011[10]).

There is a dire need for us to move away from statistics that sound nice as a punch line but do little to solve the problem at hand. Community mental health programmes are not the panacea for the issues but can go a long way in providing awareness of mental illness and lead people to seek help when they know someone is ill. The need for a mental health component to be put into National general health programmes in addition to the National Mental Health Programme shall help in mental health coming out of the incubator it is placed in and help it breathe freely with other medical counterparts. This will only be possible if people from the medical fraternity decide to open their doors to mental health and mental health professionals; this will help psychiatry blend with its sister disciplines rather than get the step motherly treatment it currently does (Caplan, 2013[3]).

Reduction of Stigma Faced by Psychiatric Patients and their Relatives

It is a fact that mentally ill patients do not get their due in India, like they do in the West. Schizophrenia as a diagnosis is dreaded, and for anyone so diagnosed and certified it can be the death sentence for one’s academic and work career. The portrayal of mental health as well as mental illness and mental health professionals in Bollywood movies often leads the common man to take a biased view of the mentally ill, looking at them as lunatics or rather grotesque emotionless beings who need to be locked up and shunned from society. Movies made on mental illness as a central theme often present a contorted theme in line with the brutal portrayal of electroconvulsive therapy as well as mental hospitals therein. The psychiatrist is often shown as insensitive and hand in glove with the villains in making a normal person mentally ill via torture or forced administration of shock therapy (as the movies prefer to term it), even hitting and restraining patients with chains (Bhugra, 2006[1]). Mental health legislation in India received no change until the Mental Health Act, 1987, and it has taken approximately another two and a half decades before India will have a new Mental Health Care Bill, 2013, in place.

The police and legal practitioners need to be taught about mental health and mental illness to help them deal with mentally ill patients when the need arises and thus be sensitive to their situation in general (Ganju, 2000[5]). Proper usage of terms to denote or refer to these patients needs to be taught along with meanings of the common medical terminology used to diagnose and refer to them. This, along with the community initiatives suggested earlier, will be an important stride forward toward many of the long-term goals emanating from Singh’s paper (Singh, 2014[20]).

Reduction of Indian Doctors Migrating to the West

It is true that Indian doctors often flock to the West in search of better opportunities, often with much better salaries and incomes. The value of patriotism and service to the nation is not one that can be imposed on anyone. There is a need, in greater national interest, that the seeds for national service and pride be sown early, starting in school and college and then medical school. But, of course, charity begins at home, and parents need to inculcate these values in their children. I believe we cannot stop brain drain as the lure of facilities in institutions abroad hold its charm and make many believe they can achieve great feats given a chance to exhibit prowess there. Rather, we need to help Indian doctors reach the USA and Europe and yet have a working partnership, wherein they bring back their expertise on a yearly or biannual basis. Even if we have 50%–60% of mental health professionals doing this, we can foster cross-border learning and implement the latest in India itself. We can also help many Indian doctors go for a few months to the West, come back, and implement what they learn there, after adapting the same to our systems. We also need to be open to learning from the West and adapting from there, maintaining the flexibility and cultural accommodation we need to make. We must make use of the brain drain by involving them as visiting faculty or visiting specialists to our hospitals rather than blaming brain drain for our pathetic mental health facilities. I also accept that not all Indian doctors abroad may want to share their experience with India, but there will be many wanting to lend a helping hand. All we need to do is tap those ready and harness their resources to help us here. We must also welcome doctors based abroad to come here and study cultural differences in mental illness and thereby promote academic growth at both ends. Encouraging cross-boundary research will probably help to clear the mist over the “glass” of brain drain while the “showers” or “drizzling” may continue (Mullan, 2006[12]).

Increased Prevalence of Mental or Psychiatric Disorders

I feel that most of the statistics on mental illness are either very circumscribed if correct or, if not, they do give a legitimate view of the extent of the problem. I say “circumscribed” because a number of patients with mental illness go undetected in the community. They neither seek help nor are identified by community epidemiological studies. The statistics mentioned in most hospital-based and community-based psychiatric epidemiological studies is more like the tip of the iceberg. Moreover, patients with psychiatric problems go undetected and do not come for treatment for at least a few months to a year poststart of the disorder (Henderson et al., 2013[6]). What clinicians see in private practice and what general practitioners see is merely a small fraction. There is a felt need to increase the rates of early diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in primary care settings. Training of general practitioner along with primary care health workers should help at least probable cases seek early help and treatment, which could ease the burden of chronic psychiatric illness.

Mental health epidemiology is in a nascent stage in India. It does not have good epidemiological services that provide stringent data on mental health problems the year round. It needs to train public health specialists in mental health epidemiology and develop a blue print to collect good and uniform data from all over the country to enable actual statistics reach us over a period of time. Community medicine departments all over the nation need to focus on mental health and lend their expertise to psychiatry departments, thereby fostering inter-department research and yielding sound mental health epidemiology data. This will enable judicious grant allocation and workforce allotment along with changes in the implementation of National Mental Health Programme. India also need to have separate goals in the programme for rural and urban settings as the needs are different, and the population under treatment differs from a demographic perspective. An eradication of the myths regarding mental illness and the blind faith in faith healers and black magic needs to be tackled as well. The local psychiatrist needs to be part of the community mental health epidemiology programme and team up with medical college departments and thus foster a team of dedicated and committed professionals who work toward the improvement of mental health at a national level (Math et al., 2007[11]).

Disaster-related Mental Health in India

India has a virtually nonexistent disaster-related mental health programme, although it is a country plagued by disaster and engulfed many a times in nature’s fury. The tsunami in South India, the Uttarakhand disaster, bomb blasts in various cities, communal riots, and wars such as Kargil have all besieged India from time to time. During these calamities, teams of doctors and psychiatrists visit these sites and provide mental health services, collaborating with local psychiatrists. However, there is no comprehensive disaster mental health programme in place. Disaster psychiatry is a multidisciplinary field and involves mental health professionals working hand in hand with other medical and paramedical professionals to provide relief to victims. Not many mental health professionals visit disaster sites, either due to lack of funding – this work being voluntary, or due to their own irrational fears they have failed to quell. There is a dearth of good quality disaster-based psychiatry research in India, and the vacuum needs to be filled.

There is also another area that needs to be addressed. It is the area of disaster-based intervention training including training in disaster or trauma counselling. India needs to draw inspiration from the West and their disaster management services and try to implement similar systems here. India is a fairly resilient nation and has overcome odds many a time. It needs to have methods to improve community resilience and family resilience, which will no doubt improve individual resilience. This is not a short-term goal but a long-term intervention which needs to evolve over the next few years. This will improve the ability of the nation to deal with natural disasters and reduce disaster-related psychiatry morbidity in the years to come (Rao, 2006[16], Yellowlees and Chan, 2015[24]).

Taking Psychiatry to the Masses and Making it a Household Name

I agree wholeheartedly with Singh, 2014[20], on this point. Mental health workers must remove the veil of fear that psychiatry holds and must make psychiatry a household name. There is a need to talk to a wider audience about psychiatry. Mental health workers must start from schools where students and teachers can be taught the types of mental illnesses. Psychiatry and madness must no longer be equated and psychiatrists must have a broader outlook for their specialty. Reaching out to diverse groups of people across various sectors of society will help educate and empower people to deal with minor mental health problems that come up and may not need a specialist’s intervention. Psychiatrists need to plan community intervention and mental health programmes with various groups to bring about a cascading effect and they need to think out of the box. Mental health workers must do programmes on nicotine dependence as well as managing road rage with bus and cab drivers. They must go to the marginalized sections of society and do programmes there. They must also move to orphanages, remand homes, old-age homes, and railway stations to spread awareness. They must also go to malls and huge public places and have events there. Issues such as domestic violence and child abuse need to come out of their closets as well as bringing out issues such as homosexuality and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender to the fore. Mental health workers must try to educate the masses and the classes as well, using digital media and social networking to the maximum to attain these goals. They must try to reach out to people of all ages, from children to old age, and work toward a slogan of mental health for all. They have the resources and the expertise; they need to cultivate the desire to do this. It is a task that may not earn finances but will earn name for the concerned psychiatrist. Mental health activism is new to India but needs to be cultivated. The benefits may not bear fruit for this generation but will benefit many generations to come. Novelty of ideas and invention in this area are a must for good results.

Reducing the Negativism toward Psychiatry and Reducing Anti-psychiatry Sentiment

Psychiatry will always have its critics and cynics. It is on the psychiatrists whether they want to answer their critics or shun them. On one hand, anti-psychiatry has helped the profession develop, while on the other hand, it has also given it its worst lows. It is a common misbelief that psychiatrists only give drugs and make their patients sleep while some believe they only talk and arrive at a diagnosis, without any investigation. There is a need for dialogue from a scientific perspective between psychiatry and its detractors to foster myth eradication while letting mature differences of opinion remain. The need within the media to improve its portrayal of psychiatry by having psychiatrists on their panel during the development of their programmes is a must to prevent errors in the representation of the profession. There should also be a legal scrutiny of anti-psychiatry websites which must be blocked if found unscientific and discriminatory in nature (Ingleby, 2004[8]). There are many websites which contain unscientific data with regard to psychiatry, psychiatric disorders, and psychotropic medication. They thus add to the already existing stigma and taboo of mental illness. It is imperative that these websites must be scrutinized, and matter that is biased and unscientific should be eliminated. We need to separate the myths from the facts.

The Need to Listen to Patients and Why Patients Must Be Heard

I have a great interest in reading the patient speak columns in various journals, but many of the first-person accounts are such that few patients have the courage to narrate their experiences in scientific literature. Patients afflicted with psychiatric problems do not get the same affection as patients with cancer or medical illnesses; in fact, it could lead to a lifetime of a mentally ill label and could also affect a patient from an employment perspective. There is a need for patients to come out openly without shame to mention that they have received psychiatric treatment which would serve as an inspiration to other patients affected by the same illness. There is also a need for patients to develop their own self-help groups for various psychiatric disorders, a phenomenon relatively inconspicuous in India. Patients with good insight into schizophrenia and depression need to help other patients cope with the illness. There is also a need for patient support newsletters that fulfill this need as not all patients may have access to the journals that publish patient speak columns.

Patients in India may not be comfortable to speak on a public forum as ridicule in case of psychiatric illness is not limited to the patients but can pass on to immediate and distant family members, affecting the growth and progress of children in the family with rejection in social circles and difficulty in finding good prospective grooms and brides. Few nongovernmental organizations organize award ceremonies where recovered patients who are doing well and compliant with medication are felicitated along with the doctor treating them. To have patients speak, they also need to have complete faith and trust in their doctor and the forums he/she may ask them to come to. Hence, along with the recovery process, good rapport and doctor–patient relationships are first steps in the process of enabling patients to speak fearlessly about psychiatric treatments and illness. Here, it is worth mentioning that family support is another important variable in making this happen.

The Need for Psychiatrists to Practice Psychotherapy in Clinical Practice

I could never agree more with the dictum that psychiatrists must do psychotherapy and must play an active role in the counselling process. Singh (2014)[20] is right in mentioning that psychiatrists often delegate this role to psychologists and are happy to supervise or be mute spectators; the vagaries of modern practice and patient workload have turned psychiatrists into mere psychopharmacological vending machines. Psychiatrists must do psychotherapy. They are trained for it. It is only via psychotherapy that psychiatrists will bring a humane touch to psychiatry or else they just become like doppelgangers of our medical counterparts with the “ask, talk, and prescribe” model. Psychiatrists can do psychotherapy better than anyone as their grounding is both biological and psychosocial. They can understand better than anyone else the intertwining of multiple factors in an illness. It has been my experience over the years that a psychiatrist who does psychotherapy always has a better practice as word spreads of his/her talking treatment, which patients yearn for, but do not get. The cost of psychotherapy to the psychiatrist is minimal. The setting needs table and chairs, which are already there, and the only other expenditure is speaking and words which involves neurobiological activation of the brain of the psychiatrist and the patient. It is a proven fact across thousands of studies, randomized controlled trials, and meta-analyses that a combined approach of both medicine and psychotherapy works better than any of the two alone (Huhn et al., 2014[7]). This needs to be utilized in everyday practice, and we need to throw away the garb of the psychiatrist who merely asks and prescribes.

One argument against psychotherapy being done by psychiatrists is workload. Well, in that case, simple uncomplicated patients may be referred to another therapist in the team; but it is prudent that the psychiatrist monitors therapy and takes a session by session report of its progress. It is also important that a few joint sessions be held, once in three or four sessions, as this will bolster the patient’s confidence that the psychiatrist is in the loop and that the patient is not been left at the mercy of someone else. This joint session will also be educative for both the treating specialists as they will learn and grow from one another’s expertise. Time management with specific slots for therapy will help the psychiatrist take up difficult cases for therapy and make him/her a better mental health professional, as psychotherapy is a two-way street where both patients and the treating doctor grow. General eclectic psychotherapy is better than a particular school where one can pick up the best of various types of psychotherapy and present views in a cafeteria approach to the patient. This does not undermine any school of psychotherapy but rather emphasizes that all are good when used judiciously.

Another reason for psychiatrists shying away from psychotherapy is a lack of psychotherapy training in psychiatry residency programmes. This needs serious rethinking. Psychiatry has reached a biological era and is moving toward a genetic and neuro-cognitive model, but it cannot let go of psychological factors which are paramount and run parallel to biological ones. They need is to walk hand in hand: let biology and psychology be conjoint twins, nonseparable at birth itself (Norcross, 2002[14]).

The Need to Build Psychotherapy Research

Any keen researcher will find a dearth of psychotherapy research in India and equally so worldwide. The nature of psychotherapy does not allow long-term outcome studies due to compliance and study length issues. Psychiatric research needs to not only increase work in this area but needs to do research that further demonstrates that psychotherapy alone has its own biological effects such as changes in hormonal levels or brain parameters (Brooks and Stein, 2015[2]). This will boost the image of psychotherapy as a stand-alone treatment in psychiatry and also in combination with other treatment measures. Resident doctors must be encouraged to take up psychological and psychotherapy research as a part of their dissertations and papers. Psychiatrists must work hand in hand with psychologists to reach this goal. A problem endemic in psychiatry is that psychiatrists and psychologists do not speak much to each other, and if they do, it is not always cordial or on the same wavelength (Singh and Singh, 2006[19]). We are all mental health professionals with common goals and need to work together for a better tomorrow for both patients and to improve the research output from India. Indianization of psychotherapy cannot be overstressed, and research in that area needs to be furthered. There is very little high-quality research in the Indian concepts of psychotherapy, and psychiatric research needs to cultivate trials or studies which tap that resource as well (Lambert, 2007[9]).

Commonalities in Psychiatric Phenomena (Singh, 2014)[20]

Mental status examination has always been taught in a rather stereotypical and uninteresting manner in psychiatry. It involves the dull listing of criteria psychiatrists use to diagnosis patients, being happy if they are able to put them into a box of their choice. Medical symptoms are taught differently. We often talk about abdominal pain and all the causes and differential diagnosis are discussed. We must do the same in psychiatry. Take a symptom or a mental status phenomenon and dissect and tease it inside out. Look at variations in presentation and how the same symptom presents differently at different ages as well as in different disorders. This will broaden the horizon of the psychiatrists in training and make them look at clinical diagnosis as not just a diagnostic criterion. Even symptoms such as sadness or loneliness can be dissected beautifully and studied to give a panoramic view of the path ahead. We need at some level to spruce up our thinking and look at innovative methods of teaching old phenomena (Trzepacz and Baker, 1993[22], Oyebode, 2015[15]). Mental status examination is rarely taught in a descriptive manner in psychiatry curricula. The ability to view the patient from both a psychodynamic and symptomatic perspective is a dying art in clinical psychiatry. A thorough neuropsychiatric mental status examination formed the basis of clinical examination in psychiatry earlier, but nowadays, there is a fixation on diagnostic criteria rather than clinical diagnosis of the patient. There is a need to cultivate the art of mental status examination in young psychiatry and psychology students who need to focus on descriptive psychopathology while providing both psychodynamic and neurobiological interpretations for the same phenomena.

The Need for Biology and Psychosocial Intervention to Come Together

Biological and psychosocial factors go hand in hand and this has been stressed earlier. I will reiterate this here with an analogy. Let us look at the human being who is our patient. Let us assume he/she is a box of chocolates. The human being is the box that has the chocolates. Within the box, there are various types of chocolates which are the different perceptions we can form of his/her illness. Let us say we have a case of pure anxiety. One view (psychoanalytical) is he/she is having a clash of id and superego impulses. Another view (neuropharmacological) is reduced serotonin and norepinephrine. Yet another view (learning theory) is maladaptive thoughts and schema that cloud his/her mind. A parallel path (existential) is that he/she is in a state of existential vacuum and has existential worry. Still another (life events theory) is of life events leading to this. One more view (neurobiological) is of a hyperactive amygdala and over function of the limbic system. These views, though diverse, are talking of the same presentation. Thus, multiple factors converge within the same human being. Thus, the human being who is a “box of chocolates” has many chocolates within him/her. The decoration of the box is the family support he/she has and the ribbon that ties the box is the genetics of the condition. Thus, we need to be diverse in our approach, and diversity entails an internal openness and flexibility which we need to nurture. This is something every mental health professional needs to appreciate, as it is only then that a holistic view of psychiatric phenomena can be formed.

Integration of various approaches is a must as the patient has to be viewed from a holistic perspective, and all approaches must be considered rather than just a neurobiological one. There is also a need to teach various perspectives in psychiatry curricula so that students who are new to psychiatry can open their minds to different viewpoints rather than develop a rigid affinity toward the neurobiological underpinnings of psychiatry.

Promoting Excellence in Research

It often hurts when one sees good clinicians who are excellent in diagnosis shudder from research. I always believe that clinicians make better researchers as they always have that clinical edge that can give better impetus to their research findings. One need not personally do research to be involved in it. One needs to be part of research teams, as clinicians helping conceptualize projects whose outcomes would be both clinically meaningful and beneficial while helping change the currently followed practice parameters. Another reason why people hate research is a poor knowledge or a disdain for statistics. This is coupled with a lack of experience in publishing research papers. We need to develop research teams akin to the movies where we have a preproduction, data collection, data analysis, and postdata analysis postproduction team. This thus focuses on all aspects of research ranging from conceptualization to Ethics Committee submissions to data collection and statistical analysis followed by writing and publishing and presentation of the data at national and international events. This team will develop gradually and we will have members who come and go while core members remain who rally the team to the end post. This will only come up when core researchers meet and interact with clinicians and exchange ideas without letting the ignorance of either side in some areas get in the way of meaningful discourse.

Psychiatry has not seen a single Nobel Laureate from India (Singh, 2015[21]). This can happen in the next few decades only when good research is cultivated along with a line of research that the researcher is passionate about. Any research that may provide new impetus to psychiatry must be encouraged and it is only then that budding scientists can work with a free mind and lack of fear of disapproval or refusal.

Psychiatry Departments in India

Finally, I come to some aspects of psychiatry departments in India. I am too young to comment on how departments develop, but nevertheless have some ideas I wish to share with those who are open to hearing them. Proactive approaches need to come into psychiatry departments and this will only be possible if there are heads and faculty who are themselves proactive. We often complain of lack of resources and funding. We often complain about Ethics Committees that are slow and unyielding. We often complain about staff members who are not supportive or of the opposition faced by junior staff from seniors who may at times thwart their progress. This is not the case in every department but is definitely the case in some. The biggest resource we have is we ourselves and our attitude and beliefs in any situation that no one else can change. We need to revamp the concept of team research. Usually, in many departments, there may be few people who are great clinicians and few who are academic while some who are research oriented. We need to team up and tap the potential of every faculty member in the department. The department as a whole must progress through research, not just one faculty member. Those in research have to learn to build such a culture. There is also a need for promoting interdepartmental research and the need to go back to basic neuroscience to seek answers to clinically relevant but unanswered questions. Talking of where I come from, we could have research groups such as a Mumbai Schizophrenia Research Group and Western India Mood Disorders Research Group to promote bigger and better research across the country.

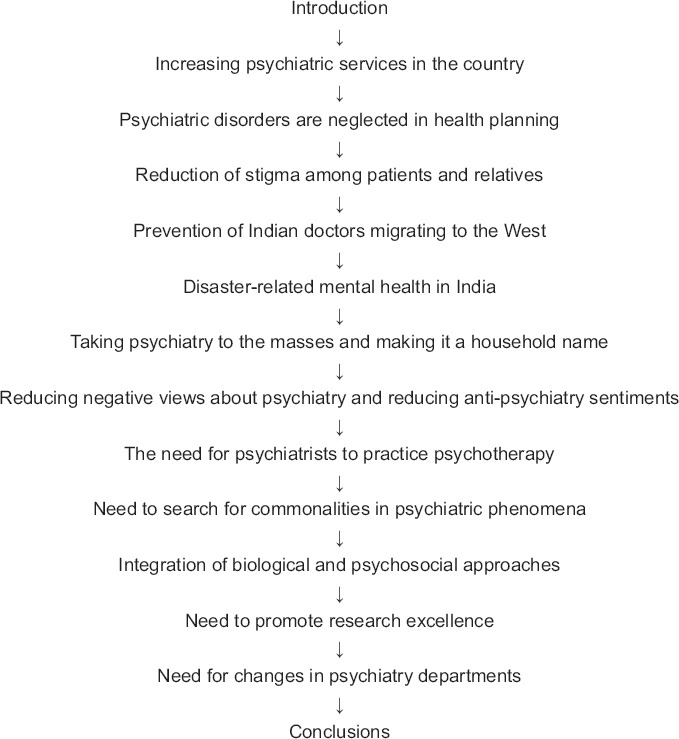

Conclusions [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the paper

The task before psychiatry today is by no means easy. There is a widespread prevalence of psychiatric disorders with almost 10% adults suffering from them, yet there is a dearth of essential psychiatric services. There is an urgent need to scale up and spread psychiatric services beyond tertiary hospitals. There is also a need to reach out to the common man and speak to a wider audience about the benefits of psychiatry and mental health. Psychiatrists need to look at the areas of disaster mental health, a relevant yet neglected area in India. Excellence in all spheres of psychiatric research needs to be fostered. Psychiatric departments need to tap research and clinical talent and sharpen it. Psychiatrists must focus not just on neurobiology but also the psychosocial dimensions of mental illness. Psychiatrists need to actively practice psychotherapy while using psychopharmacology diligently and judiciously. Psychiatry is at the doorstep of progress in various areas of mental health. It needs to improvise and sculpt now for a bright future. The task before psychiatry today is cut out – it is a daunting challenge, but the challenge, once taken up, has to be met.

Take Home Message

Psychiatry has a huge task before itself today. It needs to work at various levels to survive in the era of modern medicine.

There is a need to spread and scale up services followed by bringing mental health in the national health agenda.

The stigma and myths of mental illness need to be combated and effectively reduced while reducing anti-psychiatry propaganda.

India needs to stem the brain drain to the West and also work in the areas of disaster-related mental health intervention and psychotherapy.

There is also a concurrent need to foster academic growth and research in psychiatry.

Questions that this Paper Raises

What are the tasks before psychiatry today in India and across the globe?

Why do we need an integration of various approaches in mental illness today?

What are the steps we need to take to promote research excellence in mental health in India?

What do we need to do to reduce stigma and promote acceptance of psychiatry and mental illness?

What steps do we need to take to ensure that India may give the world a Nobel Laureate in psychiatry in the years to come?

About the Author

Avinash De Sousa MD is a consultant psychiatrist and psychotherapist with a private practice in Mumbai. He is an avid reader and has over 350 publications in national and international journals. His main areas of interest are alcohol dependence, consciousness, brain stimulation, neurobiology, and child and adolescent psychiatry. He teaches psychiatry, child psychology, and psychotherapy at over 18 institutions as a visiting faculty. He is also the founder trustee of De Sousa Foundation – a charitable trust aimed at spreading mental health awareness, training and education across all sectors. He is one of the few psychiatrists who, in addition to a postgraduation in psychiatry, has earned a Masters in Counselling and Psychotherapy, an MBA in Human Resource Development, a Masters in Religion and Philosophy, an M.Phil in Applied Psychology, and a doctorate in Clinical Psychology from the UK.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer for this paper: Anon

Conflict of interest:

None declared.

Declaration

This is my original unpublished work, not submitted for publication elsewhere.

CITATION: De Sousa A. Task before Indian Psychiatry Today: Commentary. Mens Sana Monogr 2016;14:118-32.

References

- 1.Bhugra D. Mad Tales from Bollywood: Portrayal of Mental Illness Mental Illness in Conventional Hindi Cinema. Psychology Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks SJ, Stein DJ. A systematic review of the neural bases of psychotherapy for anxiety and related disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17:261–79. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.3/sbrooks. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caplan G. An Approach to Community Mental Health. Vol. 3. Routledge Publishers; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, March D, Insel TR, Daar AS. Scientific Advisory Board and the Executive Committee of the Grand Challenges on Global Mental Health. Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature. 2011;475:27–30. doi: 10.1038/475027a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganju V. The mental health system in India. History, current system, and prospects. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2000;23:393–402. doi: 10.1016/s0160-2527(00)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson C, Evans-Lacko S, Thornicroft G. Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:777–80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huhn M, Tardy M, Spineli LM, Kissling W, Förstl H, Pitschel-Walz G, et al. Efficacy of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for adult psychiatric disorders: A systematic overview of meta-analyses. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:706–15. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingleby D. Critical Psychiatry: The Politics of Mental Health. Free Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lambert M. What we have learnt from a decade of research aimed at enhancing the outcome of psychotherapy research in primary care. Psychother Res. 2007;17:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lépine JP, Briley M. The increasing burden of depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7(Suppl 1):3–7. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S19617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Math SB, Chandrashekar CR, Bhugra D. Psychiatric epidemiology in India. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126:183–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullan F. Doctors for the world: Indian physician emigration. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25:380–93. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishtar S. Public – Private ‘partnerships’ in health – A global call to action. Health Res Policy Syst. 2004;2:5. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norcross J. Psychotherapy Relationships that Work: Therapist Contributions and Responsiveness to Patients. Oxford University Press; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oyebode F. Sim’s Symptoms in the Mind. 5th ed. Saunders-Elsevier Publishers; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao K. Lessons learnt in mental health and psychosocial care in India after disasters. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2006;18:547–52. doi: 10.1080/09540260601037961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richter J. Public private partnerships for health: A trend with no alternatives. Development. 2004;47:43–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanafelt TD, Boone SL, Dyrbye LN, Oreskovich MR, Tan L, West CP, et al. The medical marriage: A national survey of the spouses/partners of US physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:216–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh A, Singh S. Psychiatrists and clinical psychologists. Mens Sana Monogr. 2006;4:10–3. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.27599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh AR. The task before psychiatry today Redux: STSPIR. Mens Sana Monogr. 2014;12:35–70. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.130295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh AR. Blueprint for an Indian nobel laureate in psychiatry. Mens Sana Monogr. 2015;13:187–207. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.153339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trzepacz PT, Baker RW. The Psychiatric Mental Status Examination. Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. Mental Health Report. Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. WHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yellowlees P, Chan S. Mobile mental health care – an opportunity for India. Indian J Med Res. 2015;142:359–61. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.169185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]